![]()

The following text is from the NAM publication no. 50:

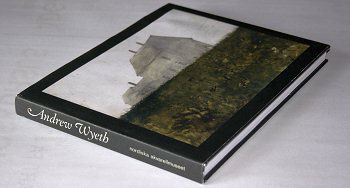

Andrew Wyeth, Watercolours from The Marunuma Art Park Collection,

The Nordic Watercolour Museum, ISBN 978-91-89477-45-2.

(The publication is sold out).

Andrew Wyeth painted naturalistic pictures. But if you visit the places he painted you notice that he created his own interpretation of them, frequently omitting details and thereby contributing to the atmosphere of the picture.

Wyeth explained this in an interview in Life: “I can’t work solely through my imagination. I have to put in a bit of reality and then I can fly free.” He also said: “The subject in itself is not important, what is important is what one can bring to the subject – what one feels for it, what one has dreamt about it.”

Many of Andrew Wyeth’s pictures originate from the countryside environment in which two families in Pennsylvania and Maine lived, and they tell continuous stories. Christina and Alvaro were brother and sister. They lived together in their childhood home at Hathorn Point on the coast of Maine. Christina is depicted in the tempera painting Christina’s World which ensured Andrew Wyeth’s breakthrough. This work was acquired by The Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1948. It is this pictorial series of the two Olson’s and their home environment that is on show at the Nordic Watercolour Museum.

Alvaro Sawing Wood is a watercolour painted in 1962 at the home of Alvaro and Christina. The painting possesses a magical glow in its balance between details and painted surfaces. One has the sense on the one hand that this is an extremely detailed picture, yet on the other that it is a very freely painted watercolour, seen for example in the sky or parts of the foreground. There are rich nuances of shading from light to dark, almost photographic in effect, and the backlighting is convincing.

Photography of

Christina’s and Alvaro’s house, Hathorn Point

Photographs of the Olson’s home show that the watercolour was presumably painted from this side of the house. The building a little further away can be the barn which stood on the farm and which Wyeth included to illustrate the chilly sea mist, a common characteristic of Maine and a typical feature in many of Wyeth’s pictures.

The next watercolour, Study for Woodstove from 1962, shows Christina sitting at her small table in the kitchen. From the door and window she can keep an eye on the few people passing outside on the road.

Several books have been written in which Andrew Wyeth describes his subject matter.1, 2 The pictures hardly need any explanation but it is in fact an advantage to hear the artist say: “I was interested in the metal plate on the stove. It gives out a hollow sound and a hollow feeling. I have always been drawn to metals and metallic sounds, to the lustre of metal, how it shines or not.” If one has ever sat by a stove one can ”hear” the picture speak.

Andrew Wyeth developed a technique using so called drybrush watercolour. Its origins may lie in his earlier tempera paintings where he wove together layer upon layer of thin lines of shifting colours to form a whole, until history and age were expressed in the picture’s surface.

In an interview with Thomas Hoving Andrew Wyeth had this to say about drybrush watercolour: “I work with drybrush when I am sufficiently emotionally engaged in a topic. I paint with a fairly small brush, dip it in the paint, spread the brush and squeeze most of the liquid and paint out of it with my fingers until there’s just a small amount left. When I move the brush across the paper it leaves at once a number of clear lines and I can then begin to shape the forms of an object to achieve an appreciable volume … Drybrush is layer on layer. One could call it a sort of weaving process. The layers of drybrush are woven into and over the broad layers of watercolour.” It was thus not always certain that a watercolour would become a drybrush watercolour. Blue Measure from 1959 (see p. 89) is one such watercolour that has undergone this development. There are large unfinished parts in it where Wyeth has worked with wet-on-wet technique, but there are also other parts where he has gone on working with saturated colours and thin brush strokes in a drybrush technique. This detail from Blue Measure shows one such part, where the sacks are built up with analogous colours, layer on layer, so that one can feel the sacks’ dry, worn and dusty structure.

The watercolour Gull Scarecrow from 1954 demonstrates Andrew Wyeth’s skill in creating a watercolour with the help of a few effects. The picture expresses a feeling of weight and the earthy colours emphasise the light of recollection. The colour scheme is typical of Wyeth. His pictures affect us with their weight. It is said of one art critic who had just visited a Wyeth exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, that he came out and shouted for joy at the sight of one of New York’s yellow taxis.

In his early watercolours from the 1930s and 1940s, Andrew Wyeth tended to use the colour spectrum more fully and exploited to a greater extent the potentials offered by traditional watercolour technique. This can be noticed in, for instance, Olson House from 1939, Two Figures Beside a Dory from 1939 and Alvaro and Others, Raking Blueberries from 1942. All these pictures strike the viewer as more anonymous.

Olson House in Fog from 1967 is a watercolour which illustrates the effect of omitted details. The building has acquired a special enclosed atmosphere. But there is at the same time a suggestion of transparency. In the bottom window on the right one can look straight through the house and out through a window in the opposite wall. This was a trick used by Andrew Wyeth in numerous pictures to create a sense of space.

In 2005 I had the good fortune to visit Andrew Wyeth. I remember him as a dynamic host with a welcoming smile. He spoke with a loud voice but lowered it now and then almost to a whisper in order to stress some detail in our conversation. He discussed the pictures hanging in his home – the mill on Brandywine River. He told me of his father n.c. Wyeth who used to say: “You should always look closer at what lies behind a painting, beneath the actual surface.” “My father was a great teacher,” he said quietly as we stood before a fresh watercolour hanging ’on trial’ in the sitting room. I believe this was a piece of wisdom that Andrew Wyeth carried with him throughout his life.

Andrew Wyeth died in 2009 at the age of 91. He kept on painting to the end, and he is buried next to his friends and models, Christina and Alvaro, at Hathorn Point in Maine.

All the works belong to The Marunuma Art Park Collection except the photography of the Olson House.

The paintings can probably be found on Google and for example via: http://www.artcyclopedia.com/artists/wyeth_andrew.html

Notes

1 Thomas Hoving, Two Worlds of Andrew Wyeth, Kuerners and Olsons, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1976.

2 Betsy James Wyeth, Christina’s World, Paintings and Pre-Studies of Andrew Wyeth, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, Massachusetts, 1982.