![]()

A small village, Chadds Ford in Pennsylvania, is the inspiration to a large number of Andrew Wyeth’s landscape paintings. The artist was born in this village and he has worked in the surroundings since he was a child. It is rather easy to find the locations behind many of his paintings, and it can be a great inspiration to be in the surroundings and see the places.

A comparison between a landscape and a painting tells much about moods and the story the artist wants to express. In the case of Andrew Wyeth this is not only a direct transformation from landscape to painting but it is also a transformation in time because he has worked in the same surroundings for more than 60 years.

The artist himself explains in his biography that it is always a disappointment to show a location to visitors because they find the place small and without any special expression compared with the “real” painting. Somehow, this is the way things should be because a location is only a source of inspiration and not necessarily an object that should be reproduced. Wyeth’s own words on the importance of the objects in the landscape are given in a recent interview in Life. “I can’t work completely out of my imagination. I must put my foot in a bit of truth, and then I can fly free”, and also: “It is not the subject, it’s what you carry to it that’s important – what you feel about it, what you’ve dreamed about it”.

Chadds Ford has changed very much during the years. It has changed from a farming area in the 1940s to a suburban area in the 1970s. This means that a comparison between the paintings and the scene today can be difficult, except for details as the old buildings. A way to come a step closer to the original objects is to look at old aerial photographs, which could be considered as a sort of time machine.

Aerial photograph of the Chadds Ford area in 1937.

Courtesy Chadds Ford Historical Society1.

(click for larger image)

The paintings are easier to understand when they are compared with Chadds Ford in 1937. It is possible to see the orchard around N. C. Wyeths studio (the studio of Andrew Wyeths father). It also shows John Andress house and the location of Snow Flurries which are both in bare field, as in the paintings, while today both locations are covered with woods. All the paintings referred to can be found on the Internet or in new or old literature. Only photos of the locations will be given here.

John Andress House

John Andress House was located monumentally in the open field in the thirties as seen in the aerial photograph. It is somehow obvious, that this farm is the background in Soaring, or more correct the “bottom”, because the tempera shows three soaring Turkey Buzzards seen from above with the ground in the bottom of the painting. A pencil sketch of Soaring is also present.

Winter Fields, 1942, does also show John Andress house. This is a very remarkable painting, especially because this tempera, together with an unfinished drybrush version, shows details of Andrew Wyeth’s working methods. The artist never allows anyone to follow the working process, but in the case Winter Fields this can be seen from the differences between the two paintings. A German book “Art USA Now”2 show the unfinished drybrush version of Winter Fields. The drybrush shows the fields seen from a height, slightly above the height of a person, and the farm is a profile in the horizon. Andrew Wyeth has told that one day he found a dead crow, which he brought to the studio where he included it into the tempera version3. This changed the tempera version to a painting which is seen in a worm’s-eye point of view, and it added a strange intensity to the scene. The drybrush version shows more details as e.g. a windmill behind the house, and some trees around the house. It is typical that the artist prefers to omit details to obtain an otherworldly intensity different from the observed reality.

Two further studies are known for Winter fields. Grasses which is a drybrush study for the grass in the foreground, and Study of a Crow which is an ink and water colour drawing.

John Andress house today. The original portion was built in 1797,

with additional construction in 1898. The property is known as a

twin house, or Father/Son house, because it is two homes that

mirror each other. It has traditional German architecture

that includes stairways in the back on either sides.

A kitchen and an upstairs addition was put on, supposedly

in the thirties, according to the present owner Geoff Snelling4,

but it is not present in the paintings from the 40s. Photo: Geoff Snelling.

One of the trees close to the house is also shown in the final version of Winter Fields. This tree has a strange deathly expression, like a whale rib stranded on a beach. The bended trunks can still be seen today.

This carriage shed at John Andress house

was probably

built in the early 20th century. The ash tree shown in

Winter Fields can be seen at the shed.

It is about 160-170 years old4.

A water colour called Andress House shows the windmill as a central part of the painting. The windmill is also present in a drybrush drawing shown in American Artist, September 19425 (probably a small part of the drybrush Winter Fields). Another painting connected to John Andress house is Andress House, 1946, which shows the entrance and the porch on the south side of the house. Finally, Andress Place is from this location.

Little Africa

Quakers originally inhabited the area of Chadds Ford. They built school buildings that were octagonal to have optimal conditions for passive solar heating and lighting. The figure shows one of those buildings remaining at Birmingham Lafayette. Others can be found in the surroundings, some of them partly integrated into private houses. When Andrew Wyeth was a child there was a location they called Little Africa one mile east of Chadds Ford. It consisted of a church installed in one of the octagonal buildings and a small black community surrounding the church served by the Negro preacher Mother Archie.

The octagonal meeting house at Birmingham

Lafayette.

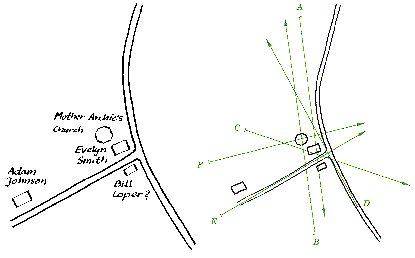

Andrew Wyeth has made a very large number of paintings in the area of Little Africa, and many of them have Mother Archies Church as a part of the composition. The following sketch shows the location and the visual angles for a number of those paintings.

Little Africa. Locations and visual angles

for a number of paintings.

Direction A

Burial at Archies, 1933

Fall at Archiers, 1937

Black Hunter, 1938

October Morning at Archies, 1950

Snow Hill, 1989 Octagonal School

Direction B

Winter Furrows, 1941

Archies Roof, 1950

Little Africa, 1984

Field Hand, 1985

Direction C

Hog Pen, 1944

Flock of Crows, 1953

The Corner, 1953

Archie’s Corner, 1953

Snow Flurries, 1953

Direction D

Road Cut, 1939

Ring Road, 1985

Plowed road near Chadds Ford

Direction E

Muddy road by Adam Johnson, 1943

Bullock Road, 1943

Adams House, 1943

The Stone House

Direction F

Blackberry Picker, 1943

Tarpaulin, 1953

Roofs at Archie’s, 1986

Inside the church

Mother Archies Church study, 1945

Mother Archies Church, 1945

The painting, Night lamp, 1950, is probably painted in the direction of northwest.

The paintings in direction A, cover a time span from 1933 and up to now (1989). Burial at Archie’s is an oil painting from 1933. Andrew Wyeth was 16 years old when he made this symbolistic painting, which shows the churchyard and the church. The painting gives the impression of a very large churchyard compared to the real size of the surroundings.

Black hunter shows Little Africa in an early egg tempera, which might be rather accurate, compared with the actual surroundings at the time. The painting shows both Mother Archie’s church and Adam Johnson’s house (Adam Johnson is a model in some of the artist’s paintings). The church was abandoned in the ‘40s but a small field with gravestones is still kept in order. The name Loper is cut in on one of the simple stones, and Loper is the family name of two of Andrew Wyeth’s models.

One of the gravestones at Mother Archie’s

church

engraved George H. Henry Loper.

Snow hill, 1989, is a late painting showing Little Africa seen from the top of Kuerners hill (direction A). It is more or less made from memories with a “rebuilding” of Mother Archie’s church, Adam Johnson’s pig house and Bill Loper’s stone house. The painting involves a number of Andrew Wyeth’s models during the years, all neighbours, and a person which is hidden. The artist himself or a coming model?

Little Africa, 1984 and Field hand, 1985 are paintings seen in direction B. A slight indication of a house opposite to the church in Little Africa may be Bill Loper’s house. In 1984 trees and houses covered the whole area. The black community had left the area many years earlier. Both Little Africa and Field hand are made from memories and perhaps from old drawings. They are made in the memory of Bill Loper who was a blacksmith and handyman in Little Africa. Bill Loper had a hook on one arm and this hook is an element in both paintings.

The water colours Flock of crows, The Corner as well as the drawing Archie’s Corner are the basis of one of Andrew Wyeth’s main pictures Snow flurries. The surroundings for those paintings are today covered with large trees, and the scene has a driveway to a house built at the hill, direction C. The aerial photo shows that the surrounding were bare fields in 1937 as shown in the paintings. The broken stone house in Archie’s Corner is Bill Loper’s house.

A photograph taken in the direction of Snow

Flurries.

It is not possible to see the fields in this photo, but

the aerial photographs from 1937 show that the

fields were bare at that time. The remains of Mother

Archie’s church are seen in the foreground. The base of

the clapboard house is situated between the church and

the road connection between Ring Road and Bullock Road.

The clapboard house burned down in 1954, and the church

was abandon at the same time.

At least three paintings showing Mother Archie’s church from the south part of the Ring Road (in direction D) have been published. Road Cut shows the surroundings of Little Africa in 1940. The picture is one of Andrew Wyeth’s early egg tempera, and it is in a slightly different style compared with the present paintings. It is seen that the scenery was very open at that time with a possibility to observe a number of hilltops far away in the horizon (Chadds Ford is often described as being located in “the rolling hills” of Pennsylvania). The landscape and the painting technique in the water colour Plowed Road near Chadds Ford also made in direction D, indicate that the painting is from the forties or the fifties. The painting shows all the buildings at Archie’s corner.

Ring Road from 1985 shows a lifelong integration of the artist’s work in Little Africa. The fields are open in the painting as it was in forties, but the church is shown as it is today. The hill behind the church, Kuerner’s Hill, has a few pine trees on the top, as it is today, but surrounded by open fields as it was earlier before the houses were built. The figure shows the Ring Road today (with a road sign slightly different from the one in the painting Ring Road). It is impossible to see the church from this part of the road due to all the trees in the area.

Ring Road seen in direction D.

A few more paintings will be mentioned to complete the description of Little Africa. A painting made at Bullock Road, Muddy Road by Adam Johnson, shows the surroundings in 1943 (Direction E). A watercolour called Roofs at Archie’s from 1986 (Direction F) is made from memories, because it shows Mother Archie’s church and Evelyn Smith’s clapboard house as they were before 1953. This is a flashback which shows that the surroundings of Chadds Ford are more a source of inspiration than a physical model for the artist.

The last painting to be mentioned from Little Africa is Night Lamp from 1950. It shows Mother Archie’s church at night with light coming out in all directions from the windows. Wyeth’s thoughts when he saw the scene were that the whole building was turned into a lamp, therefore the title.

The last figure shows Kuerner’s Hill seen from the Ring Road north of Little Africa.

Kuerner’s Hill seen from Ring Road. Turkey

Buzzards are

circulating in the sky as in the painting Soaring.

The photos from Chadds Ford are all very green because they are taken in September (except the two photos from John Andress house). Andrew Wyeth’s paintings are often made in the wintertime, and they are consequently more earth coloured. He celebrates the bleak landscape of late autumn and winter, and his paintings comprise a lifelong meditation on the frailty of life and the imminence of death. A painting called Blackberry Pickers made in Chadds Ford in the summer has the same green expression as the photos with a heavy mist of heat hanging over the scene.

Many of the paintings in the area of Little Africa can be seen the book “Close Friends”6.

Literature

1 Furst, Karen Smith, Around Chadds Ford, Images of America, ISBN 0-7385-3645-8, Arcadia Publishing, 2005

2 Weller, Allen S., Art USA Now, C. J. Bucher AG Luzern, Schweiz, 1963

3 McCord, David, Andrew Wyeth, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, ISBN 0-87846-051-9, New York Graphic Society, 1970

4 Snelling, Geoff, Private communication 2005

5 NN, Andrew Wyeth – One of America’s Youngest and most talented artists, American Artist, September, 1942

6 Wyeth, Andrew, Close Friends, ISBN 0-295-98039-7, University of Washington Press, 2001